Right View - Understanding Suffering and its Cause

The Gradual Training: Starts at Right View

When the Tathāgata first began teaching his disciples, he focused on establishing Right View as the foundation of practice. For many, cultivating right view required more effort and insight than developing the other factors of the path, making it the essential starting point for those entering the teaching.

Right View is crucial because it reshapes the mind’s entire orientation. Before it arises, the mind is still aiming at the wrong goal. It is still trying to secure comfort, identity, or satisfaction in the very processes that produce stress. Without Right View, the training becomes a set of techniques applied by a mind that has not yet understood what truly binds it. Once Right View is established, the motivation to practice becomes natural, the intention becomes sincere and has momentum behind it, and the path stops feeling like a self-improvement project and starts being a process of release.

Right View means seeing directly that every experience conditioned by craving is unstable and cannot deliver lasting peace, no matter how much we try to arrange or refine it. It means recognizing that the whole structure of dissatisfaction is built on craving, and that the end of craving is the end of the burden, it is freedom. This insight is what gives the rest of the path its integrity. Virtue, effort, mindfulness, concentration, all of it gains strength only when the mind knows what it is letting go of, and why.

When Right View is present, the Eightfold Path is not followed out of duty or belief, but because the mind finally understands its own predicament. The training becomes the natural response to suffering, rather than a task imposed on top of it. This is why Right View comes first, because it turns the mind toward freedom and makes the rest of the path genuinely achievable.

The Five Aggregates: Why Clinging Causes Suffering

Question: In life, there are eight sufferings: birth, aging, sickness, death, not getting what we desire, encountering what we dislike, separation from loved ones, and clinging to the five aggregates (form, feelings, perceptions, volitional formations, and consciousness). How can one truly understand the last suffering, clinging to the five aggregates? The previous seven sufferings can be felt, but it is challenging to recognize the final suffering of clinging to the five aggregates, yet it is said to be the root of all suffering. What does that mean?

Answer: The last suffering is often translated as the "clinging of the five aggregates." So, what are these five aggregates? In simple terms, they are the body, feelings, perceptions, volitional formations, and consciousness. These five phenomena constitute the five aggregates. But what are the five aggregates of clinging?

For an individual, the five aggregates of clinging are what one identifies as "me" or "mine." These include everything that people identify as themselves or as belonging to themselves. This encompasses the previous seven sufferings of birth, aging, sickness, death, not getting what we desire, encountering what we dislike, and separation from loved ones.

You might wonder why these five aggregates, the body, feelings, perceptions, volitional formations, and consciousness, are considered suffering. After all, there are moments of happiness and even times when we don't experience unhappiness at all. For example, when you're with someone you love, all aspects of the body, feelings, thoughts, and consciousness are pleasant. Enjoying good food, beautiful scenery, fragrances, massages, music, movies, and more can bring happiness. Furthermore, many times, people find themselves in states of neither happiness nor unhappiness, right?

That's true. The five aggregates of clinging can bring happiness or unhappiness and even suffering, and there are times when they neither bring happiness nor unhappiness. However, if you think about it more deeply, you'll realize that all worldly happiness is impermanent.

There are three aspects to this impermanence:

First, all phenomena or things are not lasting. Nothing can exist forever. Regardless of how much you love something, it will eventually depart from you, or you'll depart from it. There is no eternal togetherness; there is no forever. The stronger the attachment when something exists, the greater the distress when it's lost.

Second, the five aggregates of clinging themselves are impermanent. They can't last forever. The body requires constant nourishment to stay in existence, and even with that, it will eventually disintegrate in a few decades. This is what people fear: death. Feelings, perceptions, volitional formations, and consciousness are even more fleeting; they disappear in an instant. We need continuous contact with objects to maintain feelings and consciousness. It takes abundant energy to keep our imaginations and thoughts active. All of this effort is stress or suffering, and it ultimately amounts to nothing.

Third, and most importantly, even when phenomena or things continue to exist, the five aggregates of clinging still exist, and no one can remain in any form of happiness forever. Not for a lifetime, a year, a day, an hour, or even a minute. This is because, regardless of how happy you are, over time, you'll become accustomed to it and start to crave new sensory stimuli. This cycle of boredom and craving results in stress, and unhappiness.

Why is that? It's because all worldly happiness lacks the nature of true happiness. If a phenomenon or thing had the essence of happiness, it would make you happy at any time, anywhere, and under any circumstances. The moment that phenomenon arises, or you come into contact with it, you will be happy. However, in reality, the happiness derived from the five aggregates of clinging is not truly happiness. It only exists based on satisfying conditional desires. When those desires change, all you experience from these phenomena or things is stress and discomfort.

However, for a realized one who has achieved the cessation of the five aggregates of clinging, it's a different story. The happiness that arises after the cessation of the five aggregates of clinging is absolute, eternal, unchanging, and doesn't depend on any conditions. This is the nature it possesses.

It's like a person who has frostbite in the winter. When the frostbite is unbearably itchy, soaking it in hot water or warming it by the fire can bring immense pleasure. However, the person doesn't wish to keep the frostbite around to experience this pleasure continually because they know that the pleasure is actually the result of the suffering from the frostbite itself. Being free from the ailment, being unafflicted, is true happiness.

Similarly, the five aggregates of clinging also bring some happiness. But for someone who has realized the cessation of the five aggregates of clinging, these aggregates are like the ailment, like frostbite, and the root of unhappiness and suffering. Their nature is suffering. So, to truly understand this eighth suffering, one needs to realize the cessation of this eighth suffering, which is what the enlightened ones refer to as Nibbana.

SN22.56: In the Upādānaparipavatta Sutta the Tathagata explains that he did not claim enlightenment until he fully understood the Five Aggregates in their four aspects: understanding each aggregate, its arising, its cessation, and the path leading to its cessation. True understanding and practice leads to disillusionment, dispassion, and cessation of clinging, resulting in complete liberation and the end of the cycle of rebirth.

Suffering: What Does It Really Mean?

From a modern perspective, suffering is often understood as intense physical pain or emotional distress. However, in the time of the Tathāgata, the word dukkha carried a much broader and deeper meaning. It was not just a description of unpleasant feelings but pointed to an ongoing process, the result of causes and conditions. It included unease, discomfort, fear, dissatisfaction, restlessness, and even a subtle sense that something is missing or incomplete, that life lacks inherent fulfillment even when things appear to be going well.

The Tathāgata revealed the unsatisfactory and unstable nature of all conditioned phenomena, which manifests in three fundamental types, each arising from ignorance of the true causes of suffering.

- The Common Suffering of Life (Dukkha-dukkha)

This is the most apparent and universally recognized form of suffering. It includes birth, pain, injury, fatigue, aging, sickness, and death, the unavoidable realities of embodied existence. Regardless of one’s wisdom or ignorance, these forms of suffering are experienced simply by being alive in a conditioned body. They are the visible signs of impermanence that touch all beings.

However, even though suffering is inherent in being alive, the ordinary person adds a “second arrow.” Beyond the unavoidable pain of physical experience, the mind reacts with resistance, fear, and aversion, creating an additional layer of distress. This is the mental suffering born of reaction, the extra burden we add to the natural pain of existence. Ignorant of the fact that the unavoidable pains of life become greatly intensified by the mind’s resistance to them.

2. Suffering of Change (Viparinama-dukkha)

This type of suffering arises from ignorance of conditionality. To the ordinary person, it appears as if happiness or unhappiness is caused by things outside themselves, as if the world’s objects, people, or events possess inherent good or bad qualities.

They believe suffering comes from loss or change: when a loved one turns away, when appearance fades, when success declines, when conditions no longer align with their wishes, or when the world fails to meet their expectations. They grieve, lament, and despair because they see change as something happening to them.

For an ordinary person, the problem is seen as "out there" something happening outside of them. Life is seen as filled with situations that cause pain. The ordinary person sees suffering as something that happens "to" them, something created by conditions of living in the world. Their attention is on events, not on the process of how the mind relates to them.

This kind of suffering is mental in origin. It arises not from events themselves but from wrong views, craving, and clinging to what is unstable. When the mind projects permanence or selfhood onto what is impermanent, disappointment is inevitable.

For one practicing the Dhamma, perception shifts inward. The practitioner starts to see that most suffering is not caused by circumstances, but by the way the mind reacts to them. They begin to see that because of wrong view, craving, and clinging, the mind fabricates tension even around simple, neutral experiences.

Through mindfulness and investigation, the practitioner sees that suffering is not inherent in the things of the world. The practitioner learns to observe how thoughts, emotions, and reactions arise and pass according to conditions. They understand conditionality not merely as an intellectual concept but through direct observation of how dukkha arises in the mind from clinging to what is impermanent.

3. Suffering of Conditioned Existence (Sankhara-dukkha)

Beyond physical and reactive suffering lies a deeper and subtler layer, one that only becomes clear through profound insight. This is the suffering inherent in how our mind constructs experience. It does not arise from wrong view or mental reactivity, but from the nature of the Five Aggregates themselves.

The body, feelings, perceptions, mental habits, and consciousness are not what they appear to be. They are not the result of ultimate reality; everything we experience is constructed by the mind, shaped by conditions, ingrained memories, and limited sensory input.

In other words, the Five Aggregates are not reality itself; they are the mind's conditional recreation of reality based on ingrained memories and limited sensory input.

Because what we experience is the aggregates and not true reality, even when the mind is calm and craving has been weakened, restlessness still remains, simply because the aggregates are constructed, subject to change, and incapable of providing lasting peace.

For one who has penetrated the Dhamma directly, there is a more profound understanding of suffering. The stream-enterer recognizes that even when craving and wrong view are weakened, the very structure of experience, the Five Aggregates themselves, are unstable, conditioned, and therefore unreliable.

The mind that has seen this no longer searches for permanence or satisfaction within experience. It understands dukkha not as something that happens, but as an intrinsic quality of how experience is created, a built-in limitation of what is conditioned.

The Five Aggregates: Introduction

The Tathāgata teaches that the root of all suffering lies in craving satisfactory experiences, clinging to the Five Aggregates as “me” or “mine.” But what exactly are these Five Aggregates?

Put simply, the Five Aggregates are how we experience the world: through our body, our feelings, our perceptions, our mental formations, which are our thoughts, intentions, and emotions, and through consciousness.

However, the Five Aggregates are not a representation of true reality itself; they are the mind's conditional recreation of reality based on ingrained memories and limited sensory input.

The teachings call it “clinging to the Five Aggregates” because we mistakenly take these conditional processes to be “me” or “mine.” We assume there is a permanent self at the center, an “I” that experiences everything. The Tathāgata teaches that suffering arises because we fail to see that there is no inherent self behind experience, only conditional processes. It is not that an “I” does the perceiving; rather, the very process behind perceiving creates the sense of “I.”

Instead of a continuous consciousness observing everything from the background, the teachings tell us that consciousness is a moment-to-moment process arising based on causes and conditions. Each contact, whether with a sight, a sound, a thought, or a memory, gives rise to a fresh moment of feeling, perception, intention, and consciousness. These are not the actions of a self, but conditions arising dependent on other conditions.

In other words, experience is not being generated by an “I” interacting with the world; it unfolds through a web of past causes, intentions, desires, habits, and memories. These collected influences form what we call the Five Aggregates. They are not “me.” They are not “mine.” They are not fixed or permanent. They are conditioned processes, mistaken for a solid “me” experiencing the world.

Now, let us look more closely at each of these Five Aggregates in turn.

Depending on the eye and forms, eye-consciousness arises; the meeting of the three is contact; with contact as a condition, there is feeling; what one feels, one perceives; what one perceives, one thinks about; what one thinks about, one proliferates. From that as a source, perceptions and notions born of proliferation beset a man regarding past, future, and present forms cognizable through the eye.

MN18

The Five Aggregates: Form

Form refers to the physical aspect of experience, including the body, the sense organs, and all material objects of the world—everything that can be seen, heard, touched, tasted, or smelled.

Each of the six senses perceives its own type of form: the eye perceives light waves, the ear perceives sound waves, the nose perceives odors, the tongue perceives tastes, the body perceives sensations such as temperature, pressure, and texture, and the mind perceives mental images, thoughts, and ideas.

While form points to the material side of reality, the Form Aggregate is how this material aspect is experienced. It is not the physical things existing independently, but the body and its sense fields as known through the mind.

Light or sound on their own mean nothing until they come into contact with consciousness through a sense organ. We do not see color without the cooperation of eye and mind, nor do we feel touch without contact and awareness. Thus, form is never experienced in isolation; it is always dependent on the other aggregates of feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

And here we find our first real clue to why suffering arises. The mind does not experience physical reality as it is, but only its own constructed representation of it, and then clings to that construction as if it were reality itself.

The Body, a Bundle of Constantly Changing Conditions

Take the body, for example. We often think of it as a single, solid thing, as "my body." But what we call the body is a process, a continually changing collection of physical phenomena. It’s made up of about 30 trillion human cells, along with countless bacteria, fungi, and microorganisms. It includes organs, muscles, blood, hair, nails, bones, and innumerable parts we rarely even consider. Then there is genetic inheritance, evolutionary processes, and the results of countless past intentions.

So what, then, is the body really? It is not a fixed or lasting entity. It is a temporary coming together of conditions, constantly changing, subject to decay and death. The body itself is not the problem. The problem is that we cling to the mind-created perceptions and memories of the body. We identify with it, we call it “mine,” and we take it to define who we are. This craving, this clinging to the Form Aggregate, how form is experienced, is what gives rise to suffering.

A body that once felt strong becomes weak; a face that once seemed beautiful appears aged; a situation that once delighted us now brings anxiety. Because of clinging, our feelings shift from pleasure to pain and from satisfaction to disappointment, and our perceptions change just as quickly. When we cling to these fleeting experiences, wanting the pleasant to last and the unpleasant to disappear, there is dissatisfaction.

The teachings tell us that it is not physical forms that bind us, but our attachment to our perceptions of them. What traps the mind is the habit of clinging to our experiences of the body and the world, treating what is changing as if it were solid and ours to keep. By holding these passing experiences as “mine,” we create the suffering that comes from trying to hold what cannot be held.

The Hidden Weight of the Body

We live so continuously within the body that we rarely notice the subtle, constant effort it demands. The body must be maintained, balanced, and protected; muscles hold habitual tension; posture and movement require countless small adjustments; the senses respond to contact with the world; and the mind repeatedly reconstructs the sense of “this body,” its boundaries, weight, and position in space. All of this requires constant work, and all of it is inherently stressful.

Because our attention is habitually directed outward, to sights, sounds, people, and tasks, we rarely perceive this inner stress. The background strain becomes normal, invisible, simply “how it is.” And since most people have never experienced even a moment without a body, they cannot recognize the stress that comes with it.

The body is the root cause of most of our desires; nearly everything we do depends on bodily needs or bodily activity: eating, dressing, working, playing sports, seeking entertainment, preserving health, and managing our physical appearance.

Having a body sets in motion an entire web of conditions: perception, feeling, craving, identification, expectation, fear, and striving. The body is the root condition for a vast chain of mental and emotional activity. When the sense of “having a body” ceases even temporarily in practice, that whole structure relaxes, not just muscle tension, but the psychological architecture built around embodiment.

This body, householder, is afflicted, trapped within a shell, bound by aging and death. Anyone who, while maintaining this body, would claim even for a moment that it is free from affliction, what else could that be but foolishness?

SN36.6

To have a body is to abide within a chain of conditions. From the body comes contact; from contact, feeling; from feeling, craving; from craving, clinging and becoming. This is how the whole mass of stress and expectation arises.

Because most of us have never known experience apart from being in a physical body, we take this chain for granted. We think the pressure of the world, the pull of desire, and the constant managing of experience are just “life.” Yet when the sense of the body is released, even for a moment, the entire structure collapses, and in letting go of identification with it, the conditions for much of suffering naturally fall away.

The body is where craving and expectation take hold. To carry it is to carry a constant readiness to protect, to maintain, and to satisfy. When this readiness stops, there is a profound ease, as if an unseen mechanism has been switched off.

This is why the discourses describe the body as a shell of endless affliction.

The Five Aggregates: Feelings

And what, disciples, is the aggregate of feeling? It is these six classes of feeling: feeling born of eye-contact, feeling born of ear-contact, feeling born of nose-contact, feeling born of tongue-contact, feeling born of body-contact, feeling born of mind-contact. This is called the aggregate of feeling.

SN22.48

Now, let us turn to the second of the Five Aggregates: the Feeling Aggregate.

What do we mean by “feeling” in this context? In the teachings, "feeling" does not refer to emotions like sadness, anger, or joy, as we often use the word today. Instead, it refers to the immediate tone of every experience: whether it feels pleasant, painful, or neither-pleasant-nor-painful. This happens every moment we make contact with the world through any of the six senses, including the mind.

Every sight we see, every sound we hear, every thought we think, comes tinged with a feeling tone. Sometimes it’s a subtle pleasure, sometimes discomfort, and sometimes just a neutral hum in the background.

But why is this called an "aggregate"?

It’s called the Feeling Aggregate because our experience of feelings is shaped by past accumulated experiences. Through lifetimes of craving, aversion, and choices rooted in ignorance, we have built up what might be called a "volitional memory", our "karma". This memory influences how we interpret the same sights, sounds, or thoughts differently from others.

For example, someone else may hear a song and feel a pleasant feeling tone, while you hear the same song and feel a unpleasant one. The difference lies not in the sound itself, but in the stored karmic imprints that condition our feeling response.

As soon as this feeling tone appears in awareness, the mind builds upon it, giving it additional meaning. It sparks perception, recognition, and interpretation. From there, thought arises, and the mind begins to proliferate, spinning stories, shaping narratives, and constructing identity views.

So, the Feeling Aggregate is not just about present experience, it’s also a reflection of the intentions, habits, and tendencies that have been conditioned over time. Our feelings are not random. They arise because certain conditions, internal and external, meet in a particular moment. And crucially, they condition what comes next: whether we crave more, resist what is, or fall into delusion.

This is why feelings are so central in the arising of suffering.

The teachings describe how feelings arise through contact with the six sense bases, namely:

-

Depending on the eye (sight), feelings arise from visual forms.

-

Depending on the ear (hearing), feelings arise from sounds.

-

Depending on the nose (smelling), feelings arise from odors.

-

Depending on the tongue (taste), feelings arise from flavors.

-

Depending on the body (touch), feelings arise from tactile sensations.

-

Depending on the mind (thoughts), feelings arise from mental objects.

When a pleasant feeling arises in an untrained person, they delight in it, welcome it, and remain holding to it. Thus, craving arises.

When an unpleasant feeling arises, they sorrow, grieve, and lament, beating their breast and becoming distraught.

When a neutral feeling arises, they do not discern it as it really is, the arising, subsiding, and gratification of that feeling.

MN10

Feelings, the Stress of Reactivity

Just as the body, the Form Aggregate carries its own built-in strain through the work of maintaining embodiment, the Feeling Aggregate carries the stress of reactivity, the ceaseless rising and fading of pleasure, pain, and neutrality that keeps the wheel of craving turning.

When touched by a feeling of pleasure, one delights in it; when touched by a feeling of pain, one sorrows. When touched by a neutral feeling, one is confused. But when a disciple sees the rise and fall of feelings, he is freed, for he knows: ‘Whatever is felt, this too is suffering.’

SN36.6

Every moment of sense contact—a sound, a taste, or a thought—gives rise to a tone of pleasure, pain, or neither. The untrained mind cannot rest with this; it immediately leans toward pleasure, resists pain, or drifts into dull indifference. This very leaning is suffering itself.

We usually don’t notice the strain that feeling brings because it happens so quickly. The reflex of liking and disliking feels natural, and we instinctively attribute the feeling to the object or event itself, thinking the thing is pleasant or unpleasant, without realizing that the feeling has been created by the mind.

But when the mind grows still and mindfulness deepens, we begin to see that every feeling, even pleasant ones, carries a thread of tension. Pleasant feelings bring the stress of wanting to keep them, painful feelings bring resistance, and neutral feelings bring subtle restlessness or boredom. The mind is always being pulled somewhere.

When feeling quiet, when we observe it without chasing or rejecting, an unexpected ease appears, and the habitual pulling stops. Then we understand what the teachings meant when they spoke of “Whatever is felt is included within suffering.”

By clinging to feelings, we keep the wheel of suffering in motion. But when feelings are fully known, clearly seen, and released, craving no longer follows, and the whole process of becoming begins to unravel.

The Five Aggregates: Perceptions

And what, disciples, is the aggregate of perception? It is these six classes of perception: perception of forms, perception of sounds, perception of odors, perception of tastes, perception of tactile objects, and perception of mental phenomena. This is called the aggregate of perception.

Perception is more subtle than feeling. It’s the act of recognition and labeling, the way the mind interprets raw experience: “This is pleasant,” “this is danger,” “this is me,” “that is other.”

The Perception Aggregate refers to the accumulation of past perceptions. These accumulated impressions play a critical role in shaping how we interpret and react to the world in the present.

Perceptions and feelings arise together based on contact with the six sense bases:

-

Depending on the eye (seeing), perceptions of visual forms arise.

-

Depending on the ear (hearing), perceptions of sounds arise.

-

Depending on the nose (smelling), perceptions of odors arise.

-

Depending on the tongue (tasting), perceptions of flavors arise.

-

Depending on the body (touching), perceptions of tactile sensations arise.

-

Depending on the mind (thinking), perceptions of mental objects, such as ideas, memories, and concepts, arise.

The discourses describe perception like a mirage, alluring but deceptive, because it creates the world we then suffer inside.

Perception, disciples, is like a mirage. What a man with good eyesight sees in the heat shimmer, that a fool might take for water. So too, what is called ‘perception’ is empty, void, without lasting substance.

SN22.95

Perception is the mind’s act of shaping the world, recognizing, naming, and forming images out of the stream of experience. This seems innocent, even necessary, yet it carries a quiet tension: every perception builds and reinforces a world of distinctions, pleasant and unpleasant, self and other, mine and not mine. Through this continual labeling, the mind freezes fluid reality into fixed forms and then must live inside those forms.

Because this process happens instantly and automatically, we rarely notice its strain. The mind is constantly measuring, comparing, affirming, and defending its pictures of reality. We see a face and immediately recall a story; we hear a sound and name it; we meet a feeling and judge it. This endless mental shaping is exhausting, yet we mistake it for simply “seeing the world.”

When perception quiets, when recognition stops reaching for names, there’s a remarkable peace, an openness unconfined by mental images. The mind stops building and starts simply knowing. In that silence, one sees that the act of “making things into things” was itself a subtle bondage. The discourses describe perception “like a mirage” because it seduces us into chasing appearances, into believing the mind’s creations are solid.

To see perception for what it is, a mirage arising dependent on contact and memory, is to understand why it is unsatisfactory. As long as we take perception to reveal fixed truth, we must defend our versions of reality. When we see it as conditioned, we relax our grip, and that relaxation is freedom.

The Five Aggregates: Mental Formations

And what, disciples, are mental formations? There are these six classes of volition: volition regarding forms, sounds, smells, tastes, tactile objects, and mental phenomena. These are called mental formations.

SN22.79

Now we turn to the Mental Formations Aggregate, perhaps the most intricate and influential of all the aggregates.

While form, feeling, and perception describe what we experience, Mental Formations describe how we build experience, the constant undercurrent of intentions, reactions, habits, volitions, and subtle tendencies that shape the mind moment by moment.

The teachings call this the engine of becoming, the silent craftsman that fashions the sense of self and world.

Mental Formations interact closely with the other aggregates:

-

Form: Intentions influence and are influenced by physical actions.

-

Feelings: Feelings condition responses to experiences.

-

Perceptions: Perceptions guide the intentions formed by mental formations.

-

Consciousness: Mental formations shape the continuity of consciousness and are shaped by it in return.

Whatever one intends, whatever one plans, whatever one has a tendency toward: this becomes a basis for the maintenance of consciousness. When there is a basis, there is the support for the establishing of consciousness. When consciousness is established and has come to growth, there is the production of renewed existence in the future.

SN12.38

Mental Formations are the countless micro-movements of intention that ripple beneath awareness, the tightening of wanting, the resistance to pain, and the constant drive to arrange experience into something more bearable or more pleasing. They are the fabricators of the lived world.

Because Mental formations operate so continuously, we mistake them for the experience of being alive. They are the effort behind every becoming: the impulse to control, to plan, to judge, to maintain an image, and to escape what we dislike. This never-ending construction is stressful because it is compulsive, built on craving, ignorance, and the assumption of “I am.”

To understand Mental Formations more clearly, it’s important to recognize that they are deeply shaped by the accumulated momentum of past desires and intentions.

These past volitions leave behind karmic imprints, latent tendencies that predispose the mind toward certain reactions and behaviors. These tendencies don’t just sit passively in the background. They influence how we perceive the present moment and how we respond to it.

For example, someone with a strong habitual tendency toward anger might encounter a frustrating situation. The perception of that situation feels unpleasant. That feeling then gives rise to irritation. Irritation quickly conditions a new angry intention. And that intention not only leads to immediate words or actions, it also strengthens the underlying habit of anger.

This is how, over time, repeated intentions solidify into habitual mental patterns. These patterns, in turn, influence how we respond to new experiences, continuing and reinforcing the cycle of suffering.

When ignorance is present, we fabricate endlessly, constructing identities, emotions, and stories. When ignorance fades, the mind stops fabricating the unnecessary. The sense of strain, of “holding the world together,” lessens, and the mind becomes at ease.

The Five Aggregates: Consciousness

The Consciousness Aggregate refers to the mental process of awareness, of knowing. It plays a central role in generating the perception of a separate self, one that experiences, interacts with, and stands apart from the external world.

But it’s important to understand: consciousness is not a continuous, ever-present stream. It doesn’t run in the background like a single unbroken light.

Instead, consciousness arises moment by moment, like a flickering light bulb, each time there is contact between a sense base and a sense object. When the eye meets a visible form, eye-consciousness arises. When the ear meets a sound, ear-consciousness arises. And so on, through all six sense doors, including the mind.

This flickering happens with incredible speed, so fast that they give the appearance of continuity. But in truth, each moment of consciousness arises, ceases, and gives way to the next, conditioned by what came before.

And yet, because we do not see this clearly, we build a sense of identity around it. We think, “I see.” “I hear.” “I think.” But there is no fixed “I” behind these processes, just fleeting consciousness tied to contact, shaped by karma, and empty of any inherent self.

And what, disciples, is consciousness? These six classes of consciousness are eye-consciousness, ear-consciousness, nose-consciousness, tongue-consciousness, body-consciousness, and mind-consciousness. This is called consciousness.

SN22.79

Consciousness is categorized into six types, each corresponding to the six sense bases:

-

Eye-consciousness: the awareness of visible forms.

-

Ear-consciousness: the awareness of sounds.

-

Nose-consciousness: the awareness of smells.

-

Tongue-consciousness: the awareness of tastes.

-

Body-consciousness: the awareness of tactile sensations.

-

Mind-consciousness: the awareness of mental objects, thoughts, and emotions.

Each type of consciousness arises dependently upon the corresponding sense organ and object, for example, eye and form for visual consciousness, or ear and sound for auditory consciousness.

It’s also important to note that no two types of consciousness can arise at the same time. For example, eye-consciousness arises only when there is contact between the eye and a visible form. Ear-consciousness, on the other hand, arises when the ear contacts sound. These are distinct events. They do not overlap or happen simultaneously.

Rather, they arise and cease in rapid succession, one after another, like individual sparks lighting up and fading out. The mind quickly shifts attention from one sense door to another, creating the illusion of a continuous stream of awareness.

But in reality, each type of consciousness is conditioned, dependent, and momentary, arising only when the right contact occurs and ceasing just as quickly when that contact ends.

Understanding this reveals something profound: that our sense of a continuous, stable “self” is constructed from these ever-changing flashes of consciousness. There is no observer behind the process, just the process itself, arising and passing away.

It is impossible for one to know and see two objects at the same time.

MN43

Consciousness arises and passes away in each moment. The Tathāgata emphasized this impermanence:

Just as a monkey, faring through the forest, grabs hold of one branch, letting that go, it grabs another; so too, that which is called consciousness arises as one thing and ceases as another.

SN12.61

Clinging to Consciousness Causes Suffering

Consciousness is often mistaken as the ultimate self, the “knower” behind experience. But the teachings reveal that this, too, is woven out of conditions. Consciousness arises dependent on contact with an object: eye-consciousness with form, ear-consciousness with sound, and mind-consciousness with thought. When the object fades, the consciousness associated with it fades too.

Because consciousness flickers so rapidly, we experience it as a continuous stream. This illusion of continuity gives rise to the deep belief, “I am the one who knows.” Yet this “knower” is itself a fabrication, a mirroring of the contact between sense base and sense object, continuously renewed.

The suffering lies in the clinging to continuity. The mind silently works to sustain the sense of being a continuous observer, a subtle, ongoing act of fabrication. It is a quiet but constant strain, like keeping a spinning wheel in motion. Even refined states of Jhana, luminous and blissful, still depend on the maintenance of consciousness.

When this process is seen clearly, the mind naturally releases it, not by destroying consciousness, but by ceasing to identify with it.

Where consciousness is not established, and name-and-form do not gain a footing, there is no growth of birth, aging, and death.

SN12.64

This is the stilling of the most fundamental movement, the turning of awareness upon itself as “I.” When consciousness is understood as dependently arisen, the illusion of an abiding self dissolves. What remains is the peace the Tathāgata described as Nibbāna, not annihilation, but the unbinding of the mind from conditions.

When the mind sees the arising and passing of these five aggregates without clinging, the whole structure of “I” and “mine” loses support.

The stress that came from defending, maintaining, and defining the aggregates dissolves. What remains is Nibbāna, the stilling of all formations, the relinquishment of all clinging, the fading away of craving, and the cessation of suffering.

Thus, the liberation taught in the discourses is not about improving or purifying the aggregates but about seeing them clearly and relinquishing them.

The Five Aggregates: Should Not Be Mistaken as "Self"

Clinging to the Five Aggregates is the taking for granted, the assumption that there is a "self", a core identity, that experiences what is happening.

But clinging to the Five Aggregates is just that: a mistaken view. It’s the assumption that the body, feelings, perceptions, intentions, and thoughts—these aggregates—make up who we are. That they form a self, or an essence, and that this self is the one interacting with the world.

People mistake the experiences felt and perceived through the Five Aggregates as themselves interacting with something external. Suffering arises because, although there is a physical world, all experiences of that world—feelings, perceptions, thoughts, and judgments—are created in the mind and exist only in the mind.

Because this isn’t clearly seen, people pursue happiness, believing it exists in external objects or experiences. They don’t realize that happiness and unhappiness, along with all judgments, arise within the mind. These are shaped by causes and conditions, not by an underlying self nor by the objects or experiences themselves.

When we begin to contemplate the nature of the Five Aggregates, it becomes clear: what we’ve assumed to be part of the outside world are actually creations of our own minds. They are the result of past volitional memories, desires, intentions, and present cognition. In short, they are the Five Aggregates themselves, which we’ve mistaken for a "me" experiencing reality.

Through deep contemplation, we begin to see that this sense of self, a separate person interacting with the world, is an illusion caused by clinging to these ingrained mental formations and memories, clinging to the aggregates.

Nāma-Rūpa and the Roots of Suffering

In the teachings, existence is experienced through the coming together of mind and form (Nāma-Rūpa). Our experience of the physical world—forms, sounds, tastes, touches, and smells—arises dependent on the body and its sense organs. The mind does not know the physical directly; it only knows contact, the meeting of sense object, sense faculty, and consciousness. From this contact arise feeling, perception, and thought, the building blocks of mental experience. This is how the mind is constantly recreating the world internally; it constructs a representation of the physical through the lens of its own conditioning.

But this fabrication can never accurately represent physical reality. The mind only knows what arises within its own domain, a mental image, not the object itself. When we cling to mind-created perceptions, feelings, and thoughts, we cling not to the ever-changing world as it truly is, but to snapshots the mind has created.

Suffering arises because the mind’s fabrication of reality, colored by desire, aversion, and delusion, can never match the dynamic, changing nature of things. When we cling to these mental fabrications as “real” or as “mine,” we bind ourselves to a distorted world of concepts and memories, which causes suffering.

Liberation from suffering, therefore, comes from seeing directly, from knowing feelings as feelings, perceptions as perceptions, and thoughts as thoughts, without mistaking them for reality itself.

The Five Aggregates: Fabrication of Reality

To understand that experience is fabricated, consider that phenomena like time and space, and our sense of self as a separate being apart from the objects of the world, are not inherent in light waves entering our eyes or sound waves reaching our ears. This three-dimensional world, where we perceive ourselves as distinct from everything else, is constructed in consciousness.

It is a reconstruction, shaped to serve survival: to help us interact with the environment and to make potential objects of desire stand out from everything else around us.

Over time, all beings have adapted to fulfill the desire to survive, shaping how they feed, how they reproduce, what they like, what they dislike, and how they behave. This survival-driven adaptation requires the mind to ignore most of the vast sensory information available in the environment, and to enhance only what is most important, especially for feeding and reproduction.

For this purpose, the mind makes certain forms appear attractive and certain feelings pleasant, for instance, sexual pleasure to ensure reproduction, pleasant tastes for nourishing foods, and aversion toward things that signal danger. These feelings and perceptions help highlight what is important for survival, making certain objects stand out against the background of the world.

So, even at its most basic level, mere existence as a being gives rise to ordinary suffering, the physical and emotional pain experienced through birth, hunger, fear, aging, illness, and death. This suffering is intensified by the natural competition for resources among beings: the struggle for food, territory, control, and sexual partners. These natural processes are inherently unsatisfactory, for they unavoidably involve both physical and mental discomfort.

The Human Realm

In the human realm, the pressure from parents, friends, society, culture, institutions, advertising, and social media has magnified greed to levels unimaginable in earlier times. We have come to hold an unquestioned belief that happiness lies in indulging in food, sex, wealth, power, popularity, beauty, or any number of endless pursuits that feed sensual and mental cravings. Yet all these mind-created indulgences only add to our stress and place more obstacles in the way of happiness and liberation.

Yet although feelings and perceptions may seem completely natural and a necessary part of life, we rarely recognize how much inherent suffering they contain. What we find pleasant today may become unpleasant tomorrow; what once brought joy can later bring disappointment or loss. The sweetness of taste can turn to craving and overindulgence; affection can turn to attachment and fear of separation; aversion can harden into resentment or hatred. Because feelings and perceptions are constantly changing, and because we cling to them as real or dependable, they give rise to anxiety, tension, and restlessness.

The Five Aggregates: Language and the Mind Created World

Language, the tool that allows humans to communicate and interact using words, is an abstract representation of a mind-created reality. While language has made humans highly successful and efficient at exploiting their environment, it has also created a layer of abstraction in which people interact within a mind-made world, making humans even more detached from physical reality and natural forces.

Language reinforces the subject–object relationship. It strengthens the illusion that there are objects to be desired and a self who desires them, that there is a doer and things to be done, a thinker and thoughts to be thought.

Instead of seeing that all things are the result of natural causes and conditions, ever-changing and without permanence, people take things personally. They cling to words, static representations of what is fluid, and because of this clinging, words have the power to completely shape a person’s moods, thoughts, and actions, even though they are not based on any underlying reality.

We live in a mind-created world, driven by desire and detached from natural reality without realizing it. We believe that what we think and the words we speak can represent true reality, unaware that words are merely fabrications of the mind. Language gives structure to experience, but not truth to it. Words arise after perception; they point toward things, but never touch them. The moment we name a thing, we have already stepped away from the living reality of it.

Relying on words as if they hold essence, we mistake labels for life, signs for substance. We become attached to opinions, stories, and identities built on linguistic constructs, thinking that they mirror the world as it is. In doing so, we dwell not in the freshness of the present, but in echoes, concepts shaped by memory and imagination. This is proliferation of thoughts and meanings, the tangle of conceptual proliferation that fuels craving, aversion, and views.

What one feels, one perceives. What one perceives, one thinks about. What one thinks about, one mentally proliferates. With what one has mentally proliferated as the source, perceptions and notions born of mental proliferation beset a person with respect to past, future, and present forms.

MN18

This is how speech and thought propagate suffering. Words, if clung to, become barriers between mind and reality, imprisoning awareness in abstraction. We fight over words, defend views, and mistake linguistic distinctions for ultimate truths. Thus, the more we rely on language to define reality, the further we drift from seeing things as they are.

The wise, therefore, use speech not to build delusion, but to dismantle it, to guide the mind toward direct knowing. Words should be like fingers pointing to the moon: useful only insofar as they direct vision to what lies beyond them. When speech is used to reveal rather than conceal, to still the mind rather than agitate it, it becomes part of the path rather than a source of bondage.

Desires: Their Unsubstantial Nature

Now this is the noble truth of the origin of suffering: It is this craving which leads to renewed existence, accompanied by delight and lust, seeking delight here and there; that is, craving for sensual pleasures, craving for existence, craving for non-existance.

SN56.11

What the teachings call craving, delight, and lust, or greed, arises because we have not seen the true nature of desires. We fail to recognize that desires are ultimately unsatisfying, unsubstantial, ever-changing, and unreliable, and that craving can only result in stress and dissatisfaction.

Instead, we place our trust in what we experience through the Five Aggregates, believing our experiences to be substantial, real, and dependable—something we can grasp and cling to for happiness. We have not seen that the pleasurable things of the world are created in the mind and have no independent existence in physical reality.

We mistakenly believe there must be a way to get what we desire, to obtain happiness from the world by securing and controlling things. We have not realized that what we desire, what we consider happiness, the very things we try to bring under control, and even the sense of self itself are all creations of the mind. They do not exist outside the mind.

When we cling to the body, our feelings, perceptions, intentions, and thoughts, this creates the illusion of continuity and the belief in a “self” as an enduring entity with a unique essence. As a result, we unquestioningly believe our feelings, perceptions, and thoughts are real, that they are ours, and that they can be relied upon to see the truth and bring happiness. Because of this, we become entangled, lost in the pursuit of desires, all the while ignoring the stress, unhappiness, and dissatisfaction this very clinging creates.

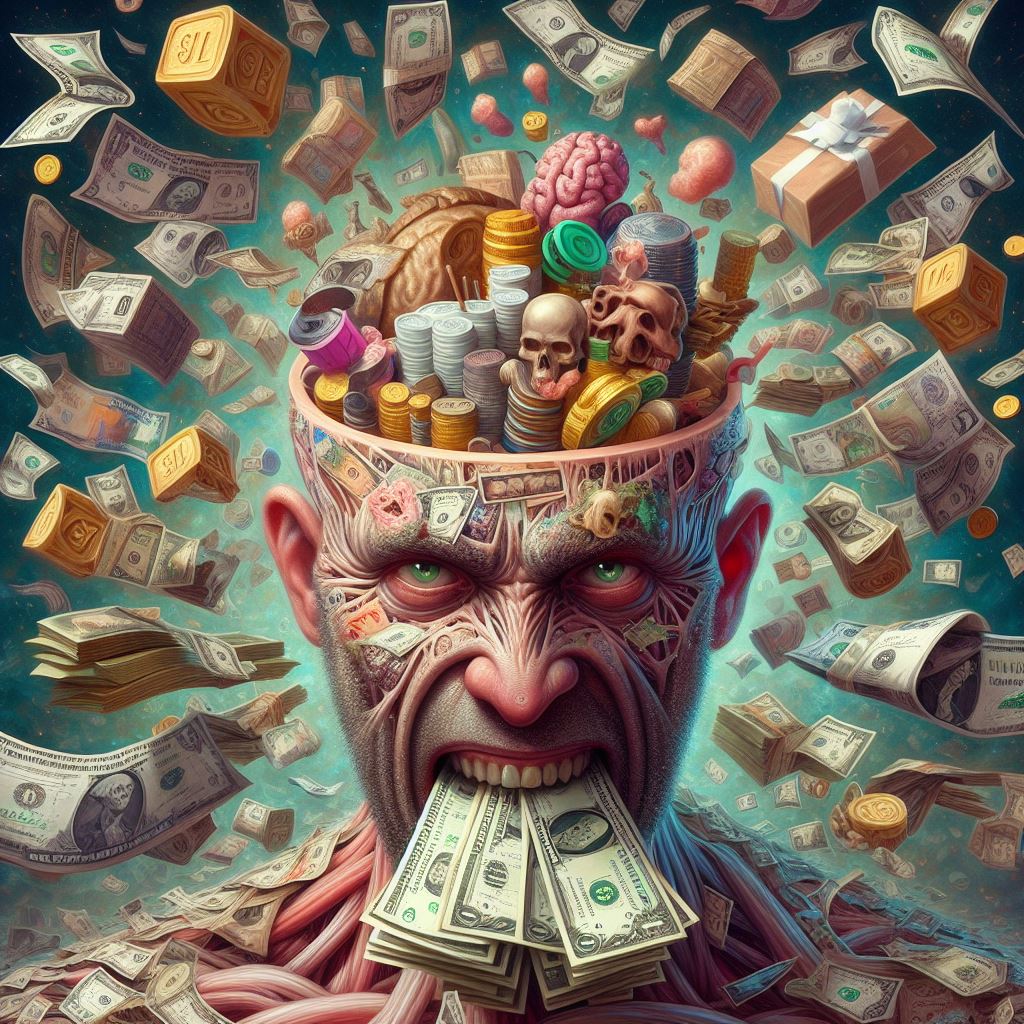

Craving Blinds Us From Reality

For example, a person blinded by the thought that money will bring happiness may chase after wealth, not to put it to practical use, but simply to amass as much as possible. In their mind, money becomes synonymous with happiness. In the process, they become blind to the stress and suffering they create for themselves, blaming problems on external circumstances or other people. Never satisfied, they continue chasing the delusion created by clinging to mind-made perceptions, feelings, intentions, and thoughts—in short, clinging to the Five Aggregates, while ignoring the unhappiness that desire inevitably brings.

In the same way, we no longer seek food simply to nourish the body; we chase after tastes themselves. Blinded by greed, we seek the idea of sex for its own sake. Greed clouds our vision so that we do not see people as they truly are, but only as they appear: “rich,” “poor,” “powerful,” “successful,” “beautiful,” or “ugly.” We chase these mind-made attributes, none of which exist in nature, and as a result, we suffer. This too is clinging to the Five Aggregates.

A liberated person, by contrast, understands that nothing in this world is intrinsically beautiful or ugly, tasty or distasteful, and that all such judgments are products of ingrained memories, volitional formations, and desires created by the Five Aggregates. Taken by themselves, they are empty of substance.

Such a person may still enjoy food, fragrances, and other experiences but sees through the distortions and enhancements of perception and thought as fabrications. Their mind does not react or cling to other people’s words, actions, or any part of existence based on these illusions. Instead, they see the underlying reality: the Five Aggregates are unreliable, fabricated, and not-self, and perceptions and thoughts are harmless when understood in this light.

Clinging to the Undesirable

Just as we cling to what we find desirable, we also cling to what we find unpleasant. Instead of seeing the underlying reality of experiences, we fixate on their perceived unpleasant features. We might, for example, reject healthy food simply because it lacks the taste we desire, ignoring the long-term harm caused by unhealthy eating.

When unpleasant sensations arise, we cling to their unpleasantness rather than seeing the truth of impermanence and not-self. This clinging only increases our stress, discomfort, and suffering.

The desire for things to be one way or another fuels unhappiness. Whenever we encounter unpleasant experiences, we try to escape by seeking out pleasant ones: food, entertainment, alcohol, drugs, sex, daydreams, and more.

But due to ignorance, we believe these pleasant experiences contain some inherent desirable quality. In truth, that desirability is a product of the mind. Such pleasures feel pleasant only because they temporarily relieve the underlying stress created by trying to satisfy desire.

And so the cycle continues: endlessly chasing desires, clinging to moments of pleasure, yet ending in dissatisfaction. This is clinging to the Five Aggregates.

Delusion persists because, even though life constantly shows us that our likes and dislikes, our views, thoughts, and actions cannot fully satisfy us or align with the truth of the physical world, we ignore this truth. Instead, we strengthen the sense of self, blindly pursuing satisfaction while overlooking the stress, unhappiness, and suffering created by that very pursuit.

Craving: Attachment to Desires

It is important to understand that the objects of the world are not the problem. Pleasure does not inherently exist in what we see, hear, or touch; it lies in how the mind reacts to these experiences.

Suffering comes from the intention behind our desires: the craving to have more, to repeat a good experience, or the urge to claim something as “mine.”

When we become attached to experiences, they begin to control us. Enjoyment shifts from something we experience freely to something we cling to. This is why the desire for sensory pleasure is not about the objects themselves, but about the way we latch onto them.

The teachings do not reject pleasure but caution against becoming entangled in it. If we misunderstand this, we might assume self-denial is the solution, but that is not the answer. The true challenge is the mind’s tendency to become obsessed, attached, and lost in craving.

We can still enjoy life wisely, appreciating good moments as long as they remain free from intoxication, identification, and craving. Of course, this is easier said than done, which is why we must examine our experiences closely to see whether craving is present.

Craving for sensual pleasure is not about sensory contact itself; it is about our mental reaction—lust, craving, attachment, delight, and obsession—toward experiences that please the senses. It manifests as:

-

The desire to repeat or prolong an experience

-

Identification with pleasure (“this is my enjoyment”)

-

Mental delight

-

Addiction-like attachment

Craving is not merely liking something; it is being drawn in by it, compelled toward it, and clinging to it. Likewise, aversion is not simply disliking something; it is being pushed away by it, resisting or clinging to its absence. Both craving and aversion bind the mind to suffering.

Contemplating Sensual Pleasures

Sensual pleasures have been described by me as having little delight, much suffering, much despair, and the danger in them is even greater.

Sensual pleasures have been compared by me to a skeleton... Sensual pleasures have been compared by me to a piece of meat... Sensual pleasures have been compared by me to a torch of grass... Sensual pleasures have been compared by me to a pit of burning coals... Sensual pleasures have been compared by me to a dream...

I have described desires as like a borrowed well... I have described desires as like tree fruits... I have described desires as like a sword's edge... I have described desires as like a spear's point... I have described desires as like a snake's head, full of suffering and trouble, with more danger therein. - MN22

Sensual Pleasures

Karma: Is Past Craving and Intentions

Ānanda, karma is the field, consciousness the seed, and craving the moisture

AN3.76

It’s important to understand that stress and dissatisfaction, although felt in the present, are the fruits of past causes, past desires, intentions, and actions that have ripened into our current experience. The circumstances of this life, and even of countless past lives, have shaped the tendencies of mind we now carry: our likes and dislikes, our views, our moods, and the very ways we interpret the world. All these together shape what we experience in each moment.

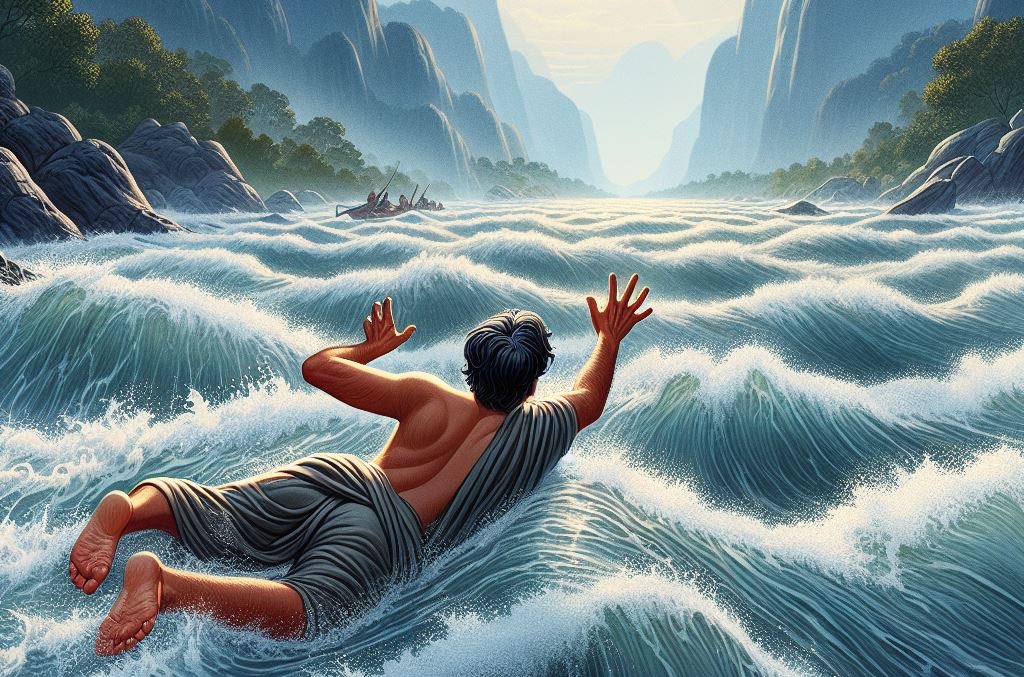

These past conditions continue to influence us because they carry karmic momentum, the residual energy of our former intentions. Each unfulfilled desire, each craving, becomes a seed seeking expression. This ongoing stream of will and becoming is what the Tathāgata called samsāra, a river of craving and striving, flowing onward from one life to the next.

Suffering arises when we fail to understand this conditioning, when we try to control our actions, emotions, and outcomes as if they were entirely within our power, unaware that our very impulses are shaped by past karma. Because of this blindness, we struggle against our own conditions, resisting what is already inevitable or forcing what is not yet possible. In doing so, we create new intentions rooted in delusion, and the wheel of dissatisfaction keeps on turning.

This gives rise to an underlying feeling of helplessness, a tension to find lasting satisfaction and to control our experience. This is samsāra itself: at times we feel submerged and overwhelmed, at times content and peaceful, but most often, we’re craving something, trying to resist the constant change. We crave, we cling, and we live in fear of being pulled under or swept away into suffering.

Karma and samsāra can be understood like seeds or intentions rooted in desire. When the right conditions appear, those seeds sprout. They ripen into stress and suffering when craving and clinging are present. For example, if we’ve formed a liking for certain foods or a dislike for particular behaviors, encountering them, through the senses or even through memory, triggers habitual reactions.

These reactions may manifest as unwholesome thoughts, speech, or actions. For more experienced practitioners, they may appear as more subtle forms of clinging, aversion, or delusion: a faint tightening, a subtle wanting, or a subtle resistance to what is.

Even though past karma might spark these unwholesome tendencies, our response in the present determines whether that karma strengthens or weakens. It is not the arising of old karma that binds us, but how we react to it.

In other words, when we first begin to practice, we can’t prevent past karma from affecting us; contact through the six senses will inevitably bring pleasure and pain. But we can stop creating new karma by changing how we respond to that contact.

It's important to understand that the Five Aggregates, everything we experience, is old karma. Only our reaction to experience is new karma. So, instead of clinging to the Five Aggregates: form, feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness—which are old karma and can't be changed, we allow any feelings, perceptions, or intentions that arise from old patterns to simply pass away. We do this by not attaching to them, not reacting to them, and not feeding them with new fuel. This is how the chain of craving is weakened, and we cease to plant new karmic seeds.

When we begin to see clearly that present experience is both shaped by the past and shaping the future, wisdom arises. We stop fighting what cannot be controlled and instead act with awareness, compassion, and wisdom. This is how we stop creating new karma.

Beings are owners of their actions, heirs of their actions; they originate from their actions, are bound to their actions, and have their actions as their refuge. Actions distinguish beings as inferior and superior.

MN135

Karma can also be understood at a simple level as the conditions that shape our identity, including unfulfilled past likes, dislikes, intentions, habits, dreams, memories, etc. This creates restlessness or agitation of the mind, a burning energy, generating volition or intentions to find satisfaction and happiness. The consequence is that we are continually seeking something to alleviate this agitation, and the mind struggles to remain calm.

Karma should be understood, the source and origin of karma should be understood, the diversity of karma should be understood, the result of karma should be understood, the cessation of karma should be understood, and the way of practice leading to the cessation of karma should be understood.

AN6.63

SN12.25: Sāriputta is asked by Venerable Bhūmija as to the origin of pleasure and pain. He replies that the Tathagata teaches that pleasure and pain originate by conditions. Moreover, all those who offer opinions on this question are themselves part of the web of conditions, as they cannot state their views without contact.

AN10.216: This Tathagata teaches that beings are the owners and heirs of their actions, determining their rebirth and future conditions based on their deeds. Actions, whether good or evil, lead to corresponding rebirths in realms of suffering or bliss. Misconduct by body, speech, and mind leads to rebirth in realms of intense suffering or as lower creatures like snakes and scorpions. Conversely, abstaining from harmful actions and cultivating compassion and righteousness leads to rebirth in blissful heavens or among noble families. Thus, one's destiny is shaped by one's actions.

To truly understand stress and suffering and to fully embrace the Eightfold Path, it’s essential to see how desire gives rise to intention. These intentions are karma; they are the volitional energies that drive us.

Intentions shape our views, our thoughts, and our habits. And over time, they lead directly to the stress and dissatisfaction we experience in the present.

By understanding this process clearly, we begin to see why the Eightfold Path is the only way forward. It offers the means to cultivate new causes and conditions, ones that lead not to further stress, but to its cessation.

Desire: Why It Causes Stress and Dissatisfaction

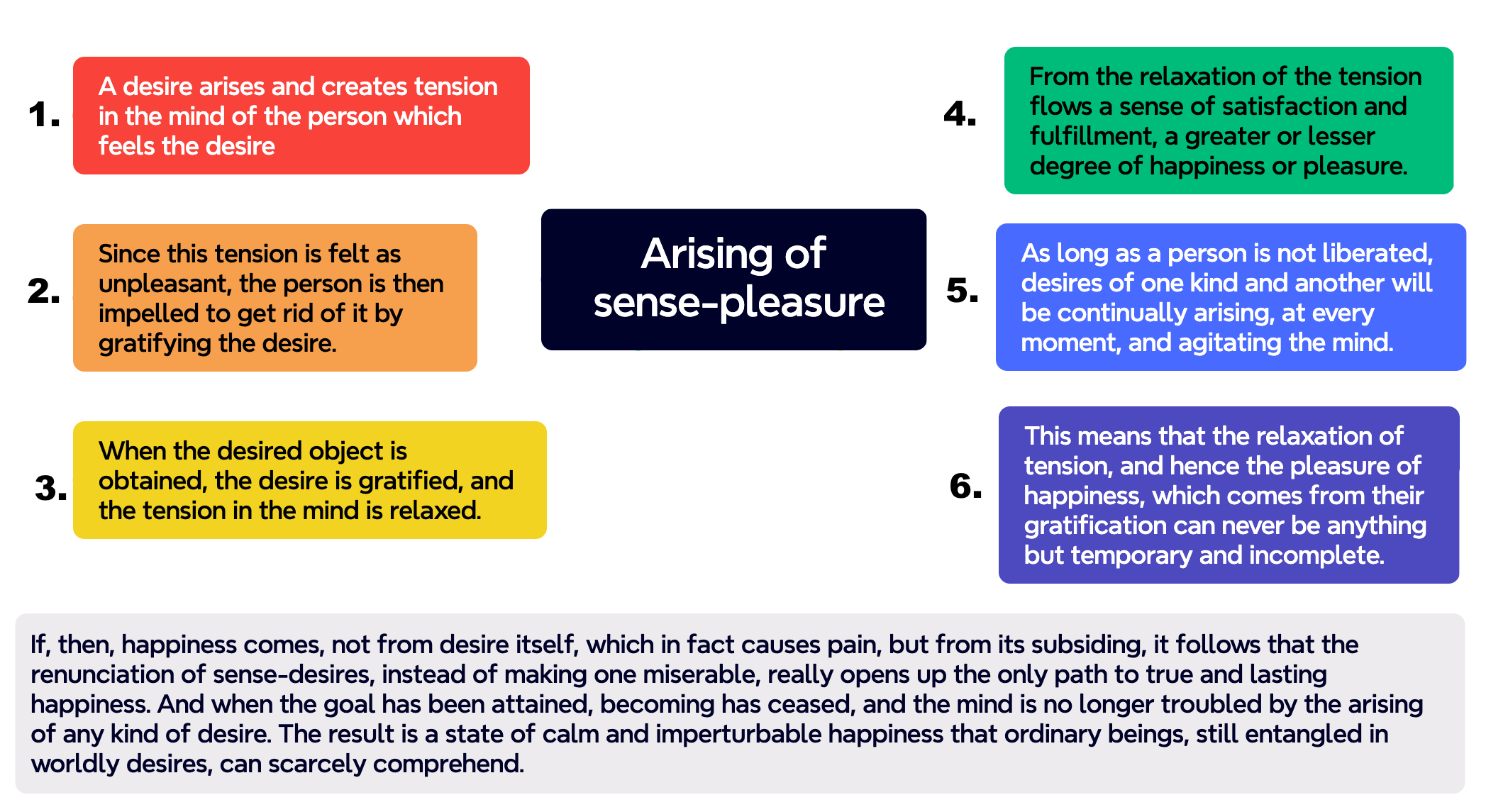

To better understand volition, stress, and suffering, consider the following diagram:

Due to restlessness from unfulfilled past desires, the mind is always seeking something to cling to, something to relieve this agitation. Based on karma, which is volition or mental energy rooted in past desires, something in our environment or memories will trigger an existing or new desire.

-

This desire causes tension or craving in the person experiencing it.

-

Since the tension is felt as unpleasant, the person is compelled to alleviate it by trying to satisfy the craving.

-

Obtaining the desired object and gratifying the craving relaxes the tension in the mind.

-

The relaxation of tension leads to a sense of satisfaction and fulfillment, accompanied by some degree of comfort. This creates the false belief that the desired object is the source of happiness.

-

As long as a person is not liberated, desires and cravings of all kinds will continue to arise, agitating the mind almost every moment.

-

Therefore, the relaxation of tension and resulting pleasure from chasing desires can never be anything more than temporary and incomplete.

For example, most people spend their whole lives chasing after things like money, material goods, beauty, status, delicious foods, winning competitions, affection, sex, or travel experiences. The expectations created, and the effort involved in trying to obtain these, cause tension and stress.

If we look carefully at this process, every time someone earns money, obtains a new possession, eats delicious food, wins a competition, obtains affection or sex, or goes on vacation, the stress from desires, cravings, expectations, and effort is temporarily relieved. This temporary relief is then mistaken as happiness obtained from that experience.

Because people believe happiness comes from making money, chasing beauty and status, receiving affection, winning competitions, or going on vacation, they repeat the cycle again and again, never achieving lasting satisfaction or happiness.

In reality, rather than recognizing that the letting go of desire and expectation and the relaxation of pressure from craving brought them satisfaction, people mistakenly believe the objects of desire themselves brought them happiness. In truth, desire is the cause of stress and dissatisfaction.

Since happiness does not come from craving or desire, which in fact causes pain, but from its ceasing, one should understand that the renunciation of craving and sense desires, far from causing misery, opens the only path to true and lasting happiness.

SN36.6: Both unlearned ordinary people and learned noble disciples experience pleasant, painful, and neutral feelings. The key difference lies in their reactions to these feelings. An ordinary person reacts to painful feelings with emotional distress and seeks relief in sensual pleasures, thus remaining attached to suffering due to ignorance of true escape. In contrast, a learned noble disciple does not react emotionally to pain, does not seek sensual pleasure, and understands the true nature of feelings, including their origin, danger, and escape, remaining detached from suffering. This understanding and detachment mark the profound difference between ordinary individuals and noble disciples in handling life experiences.

The Five Aggregates: Undependable, Unsatisfying, Not-self and Suffering

By & large, Kaccāna, this world is in bondage to attachments, clingings, & biases. But one such as this does not get involved with or cling to these attachments, clingings, fixations of awareness, biases, or obsessions; nor is he resolved on 'my self'.

He has no uncertainty or doubt that mere stress, when arising, is arising; stress, when passing away, is passing away. In this, his knowledge is independent of others. It’s to this extent, Kaccāna, that there is right view.

SN 12:15

The root of stress and dissatisfaction lies in the fundamental assumption that what we perceive through the Five Aggregates is reliable, substantial, controllable, and represents true reality or the physical world. We mistakenly equate the Five Aggregates with reality itself.

Instead of recognizing the insubstantial, not permanent, and not-self nature of experience, we overlook that all perceptions arising in the mind, including the dualities of good and bad, beautiful and ugly, and fast and slow, are judgments shaped by our conditioning, biases, and obsessions rather than by any inherent essence in objects or experiences. This clinging strengthens the illusion of a ‘me’ that possesses fixed likes and dislikes, a "me" that feels compelled to control shifting dualities, mistaking them for external realities instead of seeing them as products of the mind.

For example, once one attaches to and personally identifies with the perception of something as "good," it is inevitable that, given changing causes and conditions, this "good" attribute will eventually shift to "bad," often oscillating back and forth depending on circumstances. This constant change causes stress and suffering.

The truth, therefore, lies not in believing or disbelieving these labels of good or bad, but in not being attached or clinging to either.

'Everything exists': That is one extreme. 'Everything doesn’t exist': That is a second extreme. Avoiding these two extremes, the Tathāgata teaches the Dhamma via the middle.

SN 12.15

SN12.15: The venerable Kaccānagotta asked the Blessed One about the nature of right view. The Tathagata explained that the world largely operates on the duality of existence and nonexistence. He taught that true wisdom sees beyond these concepts, recognizing neither nonexistence nor existence of the world. The world is often trapped in attachment and identity, but right view involves understanding the impermanence of suffering without clinging to notions of self. The Tathagata emphasized avoiding the extremes of "everything exists" and "nothing exists," instead teaching the Middle Way, which links ignorance to the arising and cessation of suffering through dependent origination.

For example, although most perceptions, feelings, and thoughts naturally arise, pass away, and cease without causing stress or discomfort, the mind clings to them, wanting them to exist or not exist. This clinging is rooted in greed or aversion. As a result, a sense of self is fabricated around that very desire.

Stress arises because we cling to the arising of sensations and thoughts while ignoring their passing away, cessation, and emptiness. This attachment gives rise to unwholesome and delusional states of mind, rather than allowing these experiences to naturally fade and cease on their own.

In simple terms, when one stops clinging to the judgments and details created by the Five Aggregates and lets these mental formations fade away on their own, stress and unhappiness come to an end.

The Fires of Nibbana

For him, infatuated, attached, confused, not remaining focused on their drawbacks, the five clinging-aggregates head toward future accumulation.

The craving that makes for further becoming, accompanied by passion & delight, relishing now here & now there, grows within him.

His bodily disturbances & mental disturbances grow. His bodily torments & mental torments grow. His bodily distresses & mental distresses grow. He is sensitive both to bodily stress & mental stress.

MN149

Another critical aspect of suffering is the cumulative nature of our desires and intentions. The Five Aggregates are like burning fires: the more desire and craving we feed into them, the stronger they blaze. As the Tathāgata describes:

"His bodily disturbances and mental disturbances grow. His bodily torments and mental torments grow. His bodily distresses and mental distresses grow. He is sensitive both to bodily stress and mental stress."

Each instance of desire and clinging is like adding fuel to a fire. Over time, these accumulated fires lead to heightened stress and various bodily and mental symptoms, which can manifest as physical tension, ailments, or other issues with no apparent cause.

In simple terms, every time desire, greed, aversion, and clinging arise, our overall stress level increases. When these “fires” become too intense or overwhelming, we “blow up,” releasing stress through anger, depression, indulgence in unwholesome foods or actions, or by storing it as tension in the body, often in some combination of these.

As a result, people develop unwholesome behaviors and bad habits as coping mechanisms to manage and release underlying stress and discomfort.

It is well recognized that stress is a primary cause of a wide range of mental and physical health problems. Therefore, clinging to the body, feelings, perceptions, intentions, and thoughts, the Five Aggregates, has profound and far-reaching consequences for long-term mental and physical well-being.

Close your eyes and experience the burning

Disciples, everything is burning. And what is everything that is burning? The eye is burning, forms are burning, eye-consciousness is burning, eye-contact is burning, and whatever feeling arises with eye-contact as condition: whether pleasant, painful, or neither-painful-nor-pleasant: that too is burning.

Burning with what? Burning with the fire of lust, with the fire of hatred, with the fire of delusion. Burning with birth, aging, and death, with sorrows, with lamentations, with pains, with distresses, with despairs, I say.

Suffering: In Future Lifetimes

So far, we have only addressed stress and suffering within this present lifetime. However, the cycle of rebirth is inherently unpredictable and often leads to existences in unfavorable realms. If one could truly witness the suffering endured by beings in this and countless past lifetimes, it would become clear that even human rebirth is not exempt from profound suffering.

To fully understand the nature of suffering, we must also take into account the suffering that lies ahead in countless future lives. Only by broadening our perspective, can we begin to grasp the full scope of the Tathāgata’s teachings.

What do you think, disciples? Which is greater, the tears you have shed while transmigrating & wandering this long, long time, crying & weeping from being joined with what is displeasing, being separated from what is pleasing, or the water in the four great oceans?

As we understand the Dhamma taught to us by the Blessed One, this is the greater: the tears we have shed while transmigrating & wandering this long, long time, crying & weeping from being joined with what is displeasing, being separated from what is pleasing, not the water in the four great oceans.

SN15.3)

Disciples, this cycle of rebirths is without discoverable beginning. A first point is not discerned of beings roaming and wandering on, hindered by not knowing and fettered by craving. Disciples, whatever is seen of a destitute, miserable state, it should be understood: We too have experienced such a state in this long journey.

SN15.11

SN13.1: The Tathagata used a speck of dust on his fingernail to illustrate a point to the disciples. He compared the tiny amount of dust to the vastness of the earth, highlighting that the earth was immensely greater. Similarly, he explained that for a noble disciple who has attained right view and made a breakthrough in understanding the Dhamma, the suffering that remains is negligible compared to the vast amount of suffering that has been overcome. This demonstrates the profound benefit of realizing the Dhamma.

The Four Noble Truths

Having read or listened to the content so far, one should now possess a solid intellectual understanding of the First and Second Noble Truths:

First Noble Truth: And what is the noble truth of suffering? Birth is suffering, aging is suffering, death is suffering; sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, and despair are suffering; association with the disliked is suffering, separation from the loved is suffering; not getting what one wants is suffering. In brief, the Five Aggregates subject to clinging are suffering.

Second Noble Truth: And what is the noble truth of the origin of suffering? It is this craving which leads to rebirth, accompanied by delight and lust, finding delight here and there; namely, craving for sensual pleasures, craving for existence, and craving for non-existence.

It is important to understand that merely having an intellectual grasp of Suffering and its origin is not enough. We must deeply contemplate this understanding and observe how it manifests in our own lives until we gain direct, penetrative insight into the First and Second Noble Truths. Only then do we develop a partial Right View and Right Intention inclined toward renunciation, and truly comprehend why the cessation of suffering can be realized only through following the Noble Eightfold Path.

Third Noble Truth: And what is the noble truth of the cessation of suffering? It is the remainderless fading away and cessation of that same craving, the giving up and relinquishing of it, freedom from it, and non-reliance on it.

Fourth Noble Truth: And what is the noble truth of the path leading to the cessation of suffering? It is this Noble Eightfold Path, namely: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

The Four Noble Truths held by the Noble Ones are not static doctrines; they are practical truths that guide the ongoing cultivation of the Eightfold Path. In practice, this means continually discerning more and more subtle forms of stress and suffering, identifying their causes, and realizing their cessation through the Eight-Fold Path.

MN13: Challenged to show the difference between his teaching and that of other ascetics, the Tathagata points out that they speak of letting go, but do not really understand why. He then explains in great detail the suffering that arises from attachment to sensual stimulation.

Contemplation: Clinging to the Five Aggregates

A noble disciple understands clinging, its origin, its cessation, and the practice that leads to its cessation. But what is clinging? What is its origin, its cessation, and the practice that leads to its cessation?

There are these four kinds of clinging. Clinging at sensual pleasures, views, precepts and observances, and theories of a self. Clinging originates from craving. Clinging ceases when craving ceases. The practice that leads to the cessation of clinging is simply this noble eightfold path.

MN9

The discourses describe four ways people cling to the Five Aggregates, believing them to be the self.

First, there is clinging to the feelings and perceptions about the objects of the world, creating an identity around what is liked and what is disliked.

Second, as a result of this clinging, views arise about what is good and what is bad in the world. These views become entrenched, reinforcing the belief in a self, shaping ideas about how the world should and should not be, and how one ought to live.

Third, based on these views, habitual thoughts and routines take shape. They lead to further clinging, strengthening the sense of a self that is constantly seeking happiness and avoiding unhappiness in this world.

Fourth, the more likes and dislikes become ingrained as views, and the more these views are reinforced through habitual thoughts and actions, the deeper the clinging to the Five Aggregates becomes. One ignorantly believes that the body, feelings, perceptions, thoughts, and views are entirely real, substantial, and the self, and that they can be relied upon to avoid distress and secure happiness.